Almost exactly a year after my SponsorLink feedback post, I think I have worked out most of the issues and would like to give this another try with a completely rewritten SponsorLink v2.

A lot has happened in the intervening year, including valuable experiences trying to monetize OSS by other popular libraries (like ImageSharp, PrismLib and others). Many things stayed the same, though, including pitiful sponsoring uptick since I removed all traces mentioning the ability to sponsor my libraries from build and analyzer tools.

Just as last time, an obvious disclaimer first:

I’m not speaking for anyone but myself. I don’t represent the “dotnet OSS community”, or speak as to “how OSS should be/is done” or what is “right” or “wrong” here.

Overview

The new v2 implementation is a complete rewrite and has reoriented several areas based on the feedback I got.

Broadly, the following areas have been redesigned based on it.

Privacy and GDPR

It was a pretty bad mistake on my part attempting to make SponsorLink work too “magically” last time and just “light-up” without asking users for explicit consent on what was being done, why and allowing easy opt-out, only made worse by a poor technical choice for user identification for sponsor linking purposes.

This time around, things are much more conscientious in this regard:

- No network access is ever performed without user consent at any time

- No network access is ever needed to check for sponsorship status

- Fully random “installation id” is the only thing backend uses for telemetry

- Sponsor linking is explicitly opt-in and requires multi-step acceptance:

- On a CLI console app that syncs sponsorship status, on first use

- On GitHub.com as an OAuth app that shows what information will be shared

- Revoking access and opting out is similarly straightforward:

- CLI tool allows to remove all traces

- Directs users to relevant GitHub.com settings to revoke access

- Everything is OSS.

An explicit privacy policy is also provided, which is also shown in the CLI tool on first use.

It sounds complicated, but it actually is pretty straightforward:

dotnet tool install -g dotnet-sponsor

sponsor sync devlooped

The same tool can be used by any other SponsorLink v2 self-hosted backend.

Transparency

Another pretty bad mistake was attempting to make the system hard to circumvent. This involved some really stupid ideas like making the sponsor checking closed source and obfuscated. Bundling this with OSS libraries was just the icing on the cake of bad ideas.

The new approach is 100% OSS end-to-end: the sync tool, the backend, the sample analyzer, the manifest-based spec.

I have been asking for feedback for months now, and I feel the new approach is pretty solid. It makes things Just Work, without resorting to “security by obscurity” that we should all know is just dumb.

Scalability

Rather than attempting to offer a one-solution-fits-all approach where other potential OSS developers/organizations would rely upon my implementation, the new SponsorLink v2 instead offers a manifest-based reference implementation only, which others may self-host. The tooling is smart to detect support for the manifest and invokes well-defined endpoints that can be implemented by a user or organization in any way they like. Self-hosting of the backend reference implementation is made (fairly) straight forward as an Azure Functions app, but there’s no requirement to use my implementation at all.

Remote and local manifests are placed in well-known locations specified in the

spec, and they are standard JWT

(down to the actual claim types used, such as issuer, audience, roles and so on).

Another piece of feedback was organization sponsorships and how that would allow easier scaling in scenarios where users are just forced to use certain libraries by their employers.

SponsorLink v2 now considers the following kinds of sponsorship “roles”, in order of precedence:

user: the user is a direct sponsorcontrib: the user is considered a sponsor because it has contributed to the project via commits that have been merged.org: the user is a member of a sponsoring organization.oss: The user is a contributor to other active open-source projects.

Any combination of these roles can be present simultaneously.

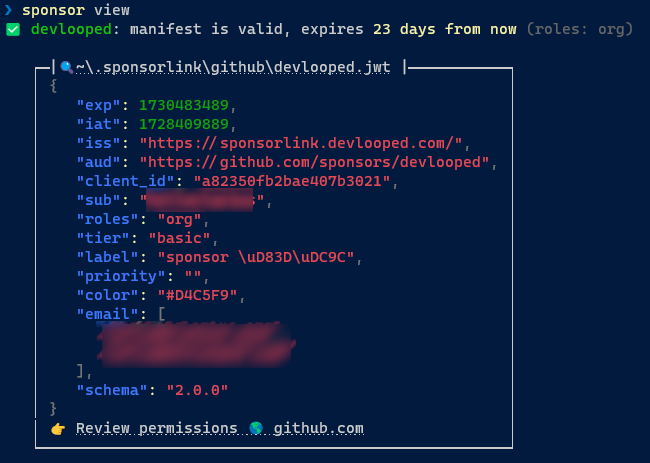

In addition, the sponsorship tiers can provide arbitrary metadata that is then persisted in the manifest as JWT claims too. For example, I use the following metadata in my sponsor tiers as a hidden HTML comment:

<!--

tier: basic|silver|gold|platinum|bitcoin

label: sponsor 💜

priority:

color: '#D4C5F9'

-->

The CLI will show the resulting JWT as follows for a sponsoring organization:

These claims can be checked by developer tooling (analyzers, MSBuild, etc.) to selectively enable features, issue warnings and whatnot.

The label and color claims are used to tag issues reported by sponsors, for example.

I’m currently not using the tier for any particular feature toggle in any of my libraries,

but it’s there if someone needs the functionality.

Fellow OSS developers

The last one (oss) can be opted-out by the self-hoster, but it’s on for my organization.

It is quite important because it means ALL contributors to any OSS projects that

provide popular nuget packages (>200 downloads/day) are considered implicit sponsors.

I always thought it was a bit silly to ask fellow OSS developers to sponsor me when I’m likely using their great libraries in turn. This fixes it for good, so if you are an OSS developer (whether original author, regular or sporadic contributor), you will never have to sponsor me, unless you want to 🫶.

It was so important for me to recognize fellow OSS developers that I now scrap nuget.org downloads at the beginning of the month and I host a page in the SponsorLink docs site where developers (or organizations) can check their stats and even share them proudly via shields.io badges entirely serverless.

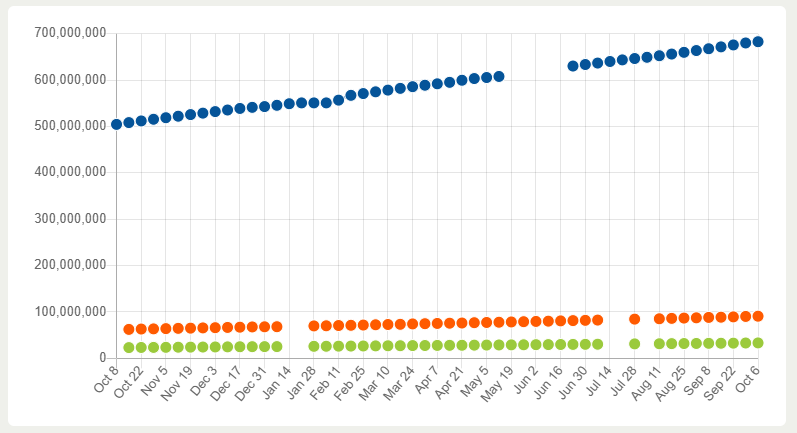

How may packages/authors fit in that “popular” category? These are the live stats:

That’s pretty massive. If you have ever contributed to a popular OSS project, you’re likely in that list. Feel free to check it out and share your stats from the docs site!

Benefits for users

It was also pointed out that it looked like sponsoring users didn’t get any benefits beyond removing annoyances. The most egregious annoyance was a one-time (for the lifetime of the IDE) build pause. As an OSS-luminary friend noted: if you’re building Swift code, the build pause will go entirely unnoticed since the build already takes forever 😂.

The previous analyzer-based approach is now just a sample that libraries may

or may not adopt. If they do, it now involves a single solution-wide, IDE-only,

never-error (even with WarningAsErrors), per-product warning when sponsorship

status is unknown. Just like before, this warning is never reported in CLI or

CI builds.

But a few new areas are now integrated into SponsorLink:

- Auto-labeling of issues and pull requests: there is even an extensible mechanism to use custom labels depending on the sponsorship tier. This feature allows improved prioritization of feedback and contributions from active sponsors.

- Real-time push notification of sponsor’s issues and issue comments by leveraging Pushover.

- Backing issues: one-time sponsorships can now be linked to an issue and become the “bounty” for it, increasing the chances it gets prioritized and fixed sooner. See Back an Issue

For now, there is no automated distribution of the bounty to contributors that send a PR that fixes the backed issue after it’s merged. I will consider this if it becomes too much manual work. For now, I’ll do this manually as needed.

NOTE: automating the distribution is non-trivial as it would require automatically sending a one-time sponsorship to the contributor, and there is no API to do that at the moment, AFAIK.

All these benefits can be trivially leveraged by other libraries that self-host the backend and configure it for their own sponsor account. This is documented in the GitHub Sponsors Reference Implementation.

I also feature active sponsors at the time of a package publishing in the readme itself (see ThisAssembly for example). This involves fetching sponsor profile image, properly formatting it for display on nuget.org (i.e. square for orgs, circles for users) and with an easy to use markdown inclusion mechanism. You can explore the approach at devlooped/sponsors, the results being something like the following in every package I publish:

This is a nice recognition to the folks that make each release possible, although not specifically tied to SponsorLink.

The Future

I was reminded recently that what I’m trying with SponsorLink will likely not bring me many friends, and may not even bring any significant revenue. I am aware of that. But still, I think it’s worth trying.

I’d like to continue creating OSS content, so for now, I’ll continue to pursue sponsorships as a potential income source. I appreciate the feedback on alternative approaches but in particular ImageSharp author’s experience switching to a paid licenses (and trying paid support before that) has convinced me that that’s not the path I’d like to take. As I mentioned in the past, you can tell from my packages, personal and organization repositories that my interests are varied and I would like to continue to explore different things rather than set up shop around a single product/project.

On Moq

I would still like to create a brand-new Moq. I have many interesting ideas to explore for it (see Moq Rebirth from way back then) and smart ways to leverage SponsorLink to provide a differentiated experience to sponsors that makes it worthwhile to contribute, as well as innovative and extensible APIs I have been mulling on for a while.

To some extent, how much time I dedicate to it might depend on sponsorships taking off, so we’ll see how v2 goes.

I’m hesitant to reintroduce even this v2 in existing Moq at this point. I’ll first collect feedback specifically for it and make a decision after a sufficient period (3 months? more? less?).

I’ve by now realized that most of the loud criticism was by a minority, and fellow OSS developers were actually quite supportive of my efforts. Downloads haven’t even noticed the drama, so I think Moq’s loudly predicted demise has been greatly exaggerated ;-)

Closing thoughts

So, I’ve embarked on this journey again. I’m excited to see how it goes. I’d say most of the feedback I got last time has been addressed, in particular around privacy, transparency, organization sponsorships and critically (for me), recognition to other OSS developers.

If you are a .NET/C# OSS developer, just pause and think about it: there’s only ~35k of us, while there are millions of developers out there.

SponsorLink is not about making money from the community, but from the companies and users that benefit from our work. It’s an exploration of a different way to monetize OSS, which might arguably fail, but perhaps it will also succeed. And if it does, it’s open for any of those ~35k authors to jump in too.

I’d love to get your feedback on this new approach. Please explore the SponsorLink docs and let me know in the GitHub repo

Happy coding!

/kzu dev↻d