I’m contributing a few hours a week on Fridays to tutor kids on programming and a bit of electronics, in what we call a “Geeks’ School” (or Escuela de Geeks). I’m always exploring ways to make it more interesting for kids (12-16yo) to learn programming. I found out that given that the cellphone (mostly Androids here in Argentina) is their primary computing device, they were instantly hooked to the MIT AppInventor 2 platform.

We’re actually using Thunkable, a fork of the original MIT AI2 that provides a nicer Material Design UI and sleeker looking client/companion app for the device. Kids have even interacted via chat directly with the site owners, which was a blast!

One of the kids wanted to build a translating app that would:

- Accept spoken spanish input

- Recognize the text and send it to a web api for translation

- Get the translated text and have the app speak it out loud

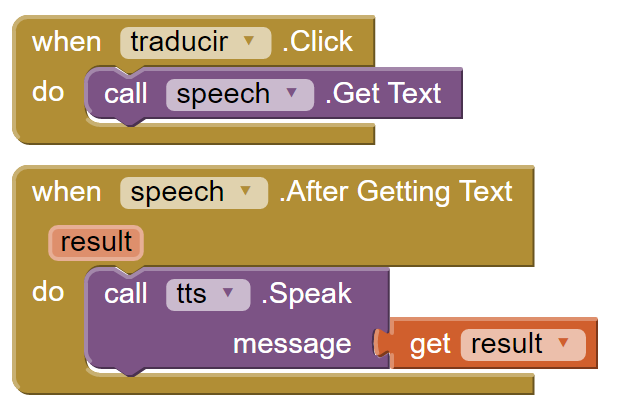

The speech recognition and text-to-speech parts were very straightforward involving just a couple built-in blocks with simple input-output connectors:

Plugging a Web component in-between the recognized (Spanish in this case) text in

when speech.After Getting Text and the call to call tts.Speak proved quite

challenging. To be clear, invoking web services by issuing POSTs and GETs is as easy

as anything else: just drop the non-visual Web component

on the designer and just call it from the blocks view. That’s the easy part. But the

key thing in invoking web services is processing its output, of course ;)

Most web APIs nowadays return plain JSON, and a quick search around the web for how to parse and consume JSON from an app yielded some very scary looking massive amount of blocks for something that is just a couple lines of code in any modern programming language.

Azure Functions to the rescue

So I remembered the Build Conference introduction of Azure Functions and chatting with the team at their booth, as well as Scott’s great introduction to Serverless Computing and this seemed like the perfect opportunity to give it a shot.

In short, what I wanted was a way to get a single JSON property value from the response of Google’s translate API. The request looks like the following:

https://www.googleapis.com/language/translate/v2?q=hola&target=en&format=text&source=es&key={YOUR_API_KEY}

And the response:

{

"data": {

"translations": [

{

"translatedText": "Hello"

}

]

}

}

It takes literally ONE line of code to retrieve the translatedText using Json.NET:

var result = JObject.Parse(json).SelectToken("data.translations[0].translatedText")

So I went to http://functions.azure.com (love the customized subdomain, as opposed to navigating the seemingly endless features of Azure in the portal) and created a new “Function app”.

NOTE: the “function app” is the actual Web API ‘site lite’ that will host the actual function (or functions). So if you name it like your function, i.e.

parsejsonthen define theparsejsonfunction, the resulting URL will look slightly awkward:https://parsejson.azurewebsites.net/api/parsejson

In my case I went for stringify for the function app name, and json for the

function name, which results in a nice looking url https://stringify.azurewebsites.net/api/json

I started directly with from the Or create your own custom function link at the bottom

of the wizard, and chose the HttpTrigger - C# template. Then I wrote the code in a

window without any intellisense (I hope that changes soon ;)) but it was dead-simple. The

whole function that takes POSTed JSON bodies and a “q=[JSON PATH]” argument

for stringifying it is:

#r "Newtonsoft.Json"

using System.Net;

using Newtonsoft.Json.Linq;

public static async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Run(HttpRequestMessage req, TraceWriter log)

{

var query = req.GetQueryNameValuePairs()

.FirstOrDefault(q => string.Compare(q.Key, "q", true) == 0)

.Value;

var json = await req.Content.ReadAsStringAsync();

return string.IsNullOrEmpty(json) || string.IsNullOrEmpty(query) ?

req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK, "") :

req.CreateResponse(HttpStatusCode.OK, JObject.Parse(json).SelectToken(query).ToString());

}

And of course you can try it out simply from curl:

curl -k -X POST -d "{\"data\":{\"translations\":[{\"translatedText\":\"Hello\"}]}}" https://stringify.azurewebsites.net/api/json?q=data.translations\[0\].translatedText

A whole speech to text translation app in less than 20 blocks

And with that, suddenly, interacting with the Web from MIT AppInventor2 or Thunkable is super straight-forward. The whole program is easy to grasp by any 12yo+ kid:

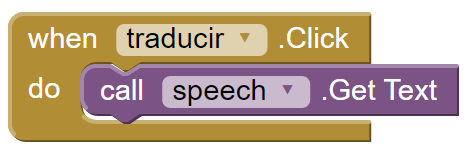

- When the button is clicked, start listening for speech:

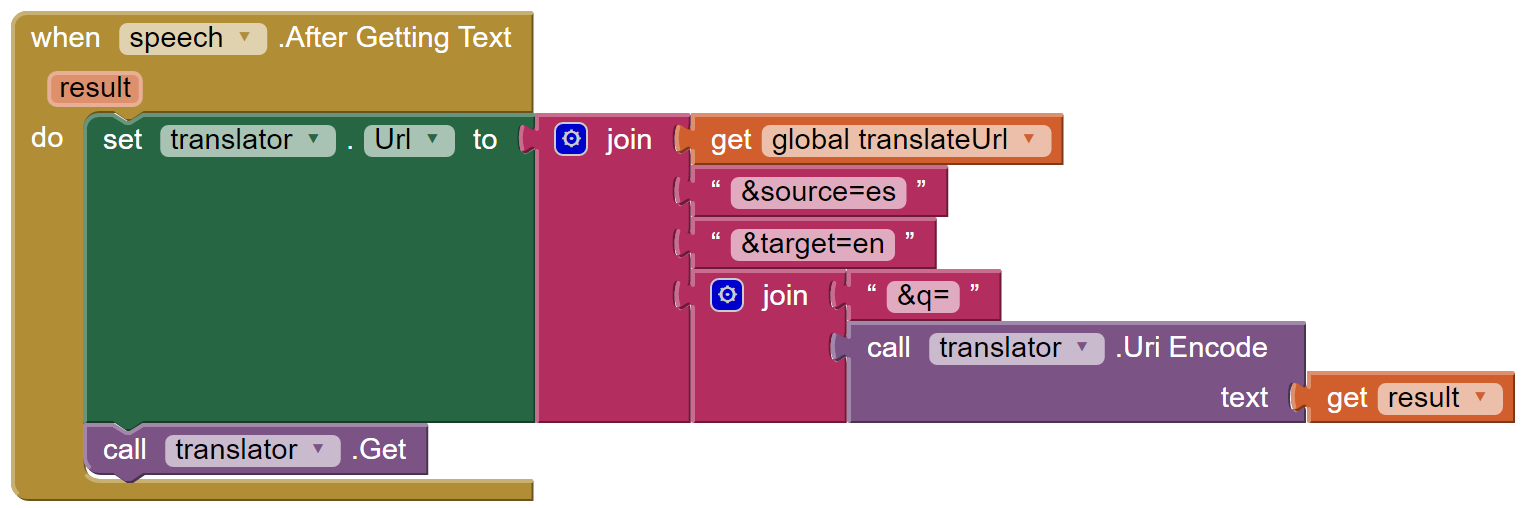

- When speech is recognized, ship it off for translation:

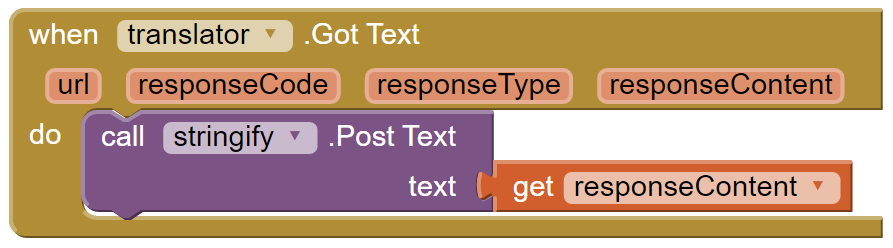

- When translation JSON comes back, ship it off for “stringifying”:

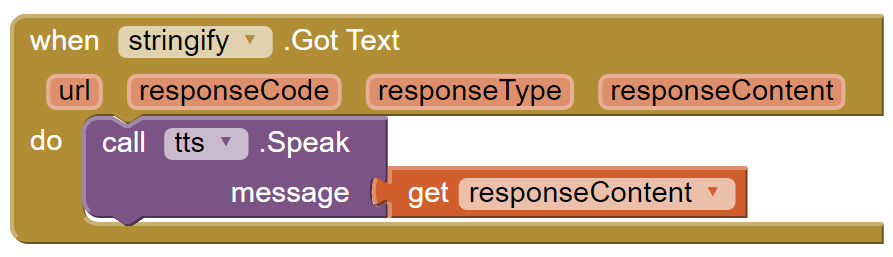

- When the simple string comes back from “stringify”, speak it out loud:

It would have taken that many blocks or more just to parse the JSON response from the translation Web API. A massive improvement by just using a little bit of serverless computing to aid in teaching :)

For other teachers leveraging MIT AppInventor for the Web, here’s the “documentation”:

- Set the

stringifyWeb component’s URL tohttps://stringify.azurewebsites.net/api/json - Append the path of the JSON value to retrieve as the query string parameter, like

?q=data.translations[0].translatedText - Use a POST Text call passing in the JSON to parse.

NOTE: if you are dealing with a single JSON web response format, the URL of the

stringifyWeb component can be set statically in the Designer pane and never changed from blocks, as shown in the above translation example.

I look forward to using Azure Functions a whole lot more. For one, I think I’ll expand the

stringify Azure Fuction app to include an xml and possibly html functions

receiving an XPath expression as the ?q= query string parameter.

/kzu dev↻d